Where the venom hides

The main protagonist of the exhibition is invisible. Hidden in special glands, the venom is used by the animals to ward off predators, defend themselves from attack and fight back. It can sometimes be lethal to humans – hence the bad reputation of spiders and snakes, which has spread to all their (mostly harmless) species. Out of the more than 3,000 known snake species, only about 450 are venomous, and in Poland there is only one – the common adder. Most snakes avoid contact with humans and attack only in defence. Instead, they help control populations of rodents and other small animals, which prevents the excessive spread of diseases and maintains ecological balance. Approximately 50,000 species of spiders have been described to date, and of these, 3% may be dangerous to humans.

Venomous animals are restrained in the use of their superpowers. After using venom, they need time to replenish it – they then remain vulnerable. Hence, they use a variety of warning signals – hissing, rattling, quick movements, displaying ‘threatening’ colouration – before going to the extreme.

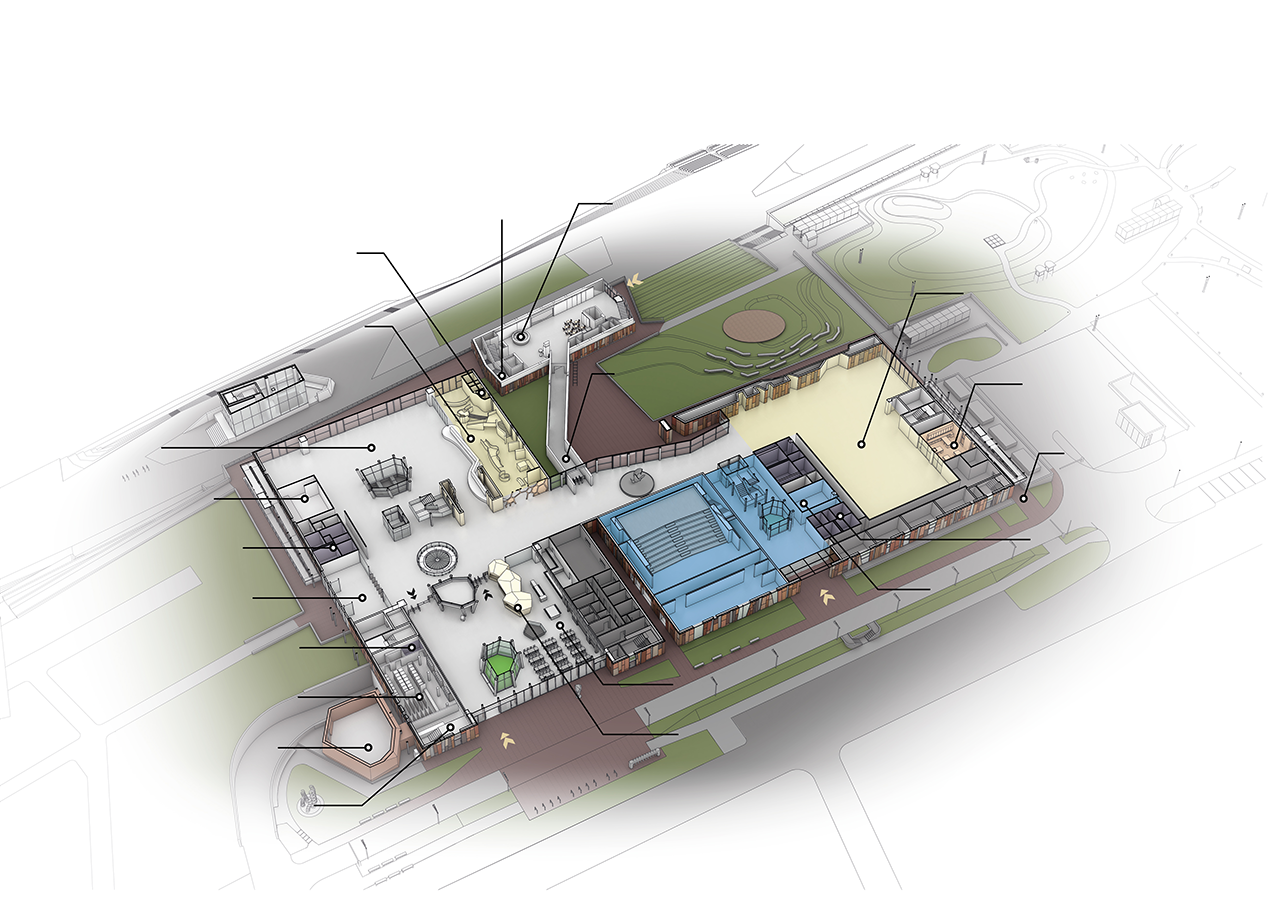

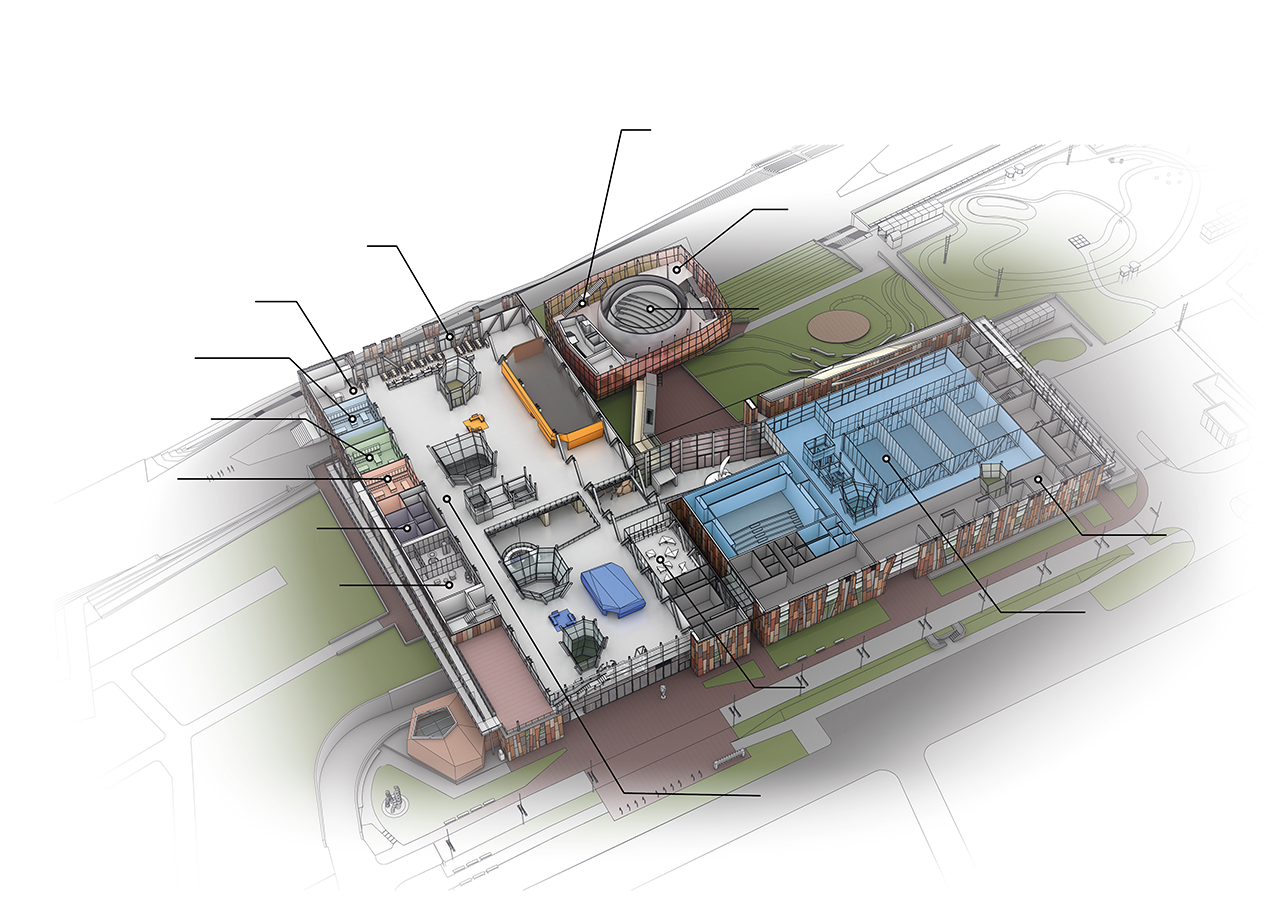

At the exhibition, the animals live in terrariums that are safe (for themselves and visitors) and allow close-up observations. You get to know where they collect venom, how they use it and what the consequences are.

Venom-based drugs

Venom can be not only life-threatening, but also life-saving. Scientists are studying individual toxins and discovering the mechanisms by which different proteins drive a variety of vital functions at the cellular level. Substances that block the nervous system are used in painkillers, and blood-thinning compounds are used in cardiology.

The animals living in the exhibition have contributed to the development of medicine. A toxin present in the venom of the eyelash viper has applications in the treatment of hypertension and heart disease. Lizards of the genus heloderma produce a peptide that promotes insulin secretion in response to a rise in sugar levels, helping to lower glucose levels in people with type 2 diabetes. The rock rattlesnake is credited with medicines that prevent the formation of blood clots and promote the breakdown of blood clots. Thanks to the Poecilotheria regalis, we may soon have new painkillers that are stronger than morphine and less addictive. The Asian forest scorpion will soon support us in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. Some peptides from its venom have also shown anti-cancer properties.

To date, around a thousand animal toxins have been tested for medical applications, and drugs containing them have reached the market. It is estimated that there are millions more substances waiting to be discovered. Unfortunately, with the disappearance of species, we are losing the suppliers of venom and with them the opportunity to discover new therapies based on yet unknown toxins. This is another reason to look at venomous animals with more sympathy and care, and to protect them.

Temporary Exhibition Partner